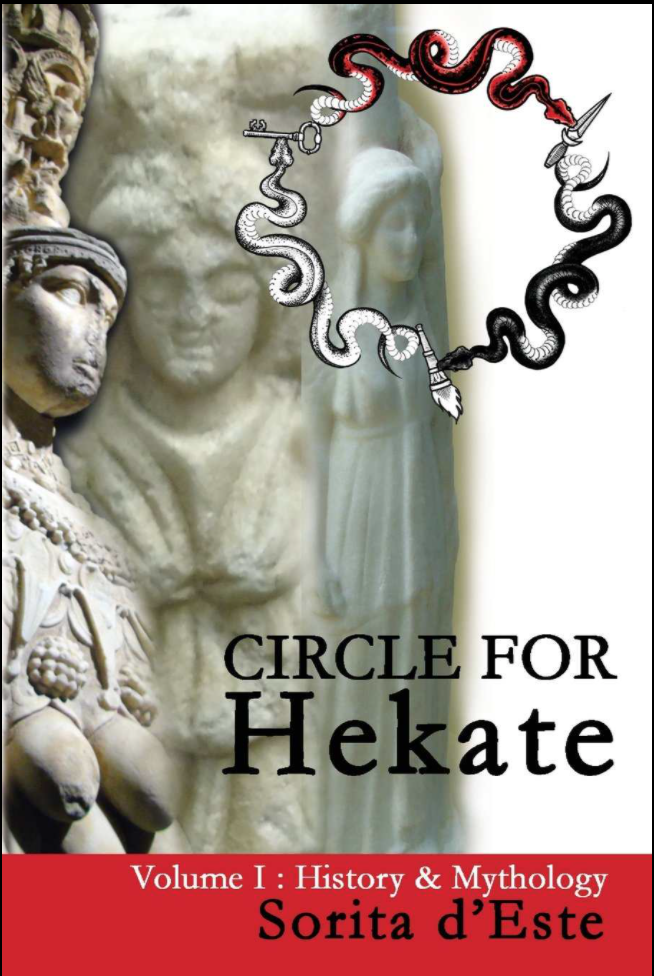

circle for hekate volume I: history and mythology

Circle for Hekate – Volume I: History and Mythology

D’Este, S. (2017). Circle for Hekate – Volume I: History and Mythology. Avalonia. ~

notes are referenced with kindle location – not page

In Hesiod’s Theogony, the earliest and most complete surviving literary account of the Greek Gods, Hekate is given the unique position of being honoured by both Zeus and the other immortal gods. “…Hecate whom Zeus the son of Cronos honoured above all. He gave her splendid gifts, to have a share of the earth and the unfruitful sea. She received honour also in starry heaven, and is honoured exceedingly by the deathless gods…”[1] She is described as a benevolent goddess, capable of granting success in many different aspects of life, as well as being a nurse to the young. Hekate is a shapeshifting goddess, manifesting in various forms and faces, single and triple-bodied, and with the heads of maidens as well as those of animals. She wields her torches illuminating the Mysteries, guiding, protecting and defending that which is under her care. She uses her serpents or whips to strike fear in those who are unprepared for her Mysteries, gifting her devotees with the ability to understand the serpent energy and knowledge. With her daggers, she cuts away that which is no longer necessary, whether the umbilical cord at birth or life itself upon death. (170)

The Theogony is one of the earliest surviving texts of the Greek language and the oldest known cosmology of the Hellenic pantheon. Using the Theogony as a starting point, this chapter examines Hekate’s divine ancestors and their respective roles. (223)

Hesiod’s description of Hekate makes it clear that he held this goddess in very high regard. (247)

Hekate is the bridge from the old to the new regime of Gods. She is a Titan goddess, the daughter of Asteria and Perses, but when Zeus takes a stand against his father, Kronos, Hekate fights against the old regime, in favour of the new. She is shown on friezes depicting the battle against the Giants, fighting alongside the other deities by using her torches as weapons. Her actions unquestionably contribute to Zeus’ victory, and in the past I agreed with the speculation that Zeus honoured Hekate in the Theogony as a result of her support for him in the Titanomachy. However, Hekate was not alone in supporting Zeus in this war, and there is no special mention or honours given to others who helped, which casts doubt on the idea of her involvement in the Titanomachy being the reason for the exalted position she is given. (262)

Mythology sometimes arises naturally, but occasionally is also purposefully created to explain a situation or to encourage specific responses in contemporary society. Stories are still being created today, and they still have the power to evoke changes in the psyches of those listening. By examining Hekate’s position in cosmology more carefully, we can investigate her family tree, and gain insights into the qualities she may have inherited from her Titan ancestors. And by looking at it from a different perspective, interesting and new connections may reveal themselves, allowing new insights and understandings to emerge. (281)

The goddess Asteria is associated with divination by dreams (oneiromancy), the starry sky, falling stars and divination by stars (astrology). Hesiod names her as the mother of Hekate, and this is repeated by later writers including Pseudo-Apollodorus and Cicero. Asteria is the sister of Leto (Latonia), and aunt of Apollo and Artemis. (294)

Cynthia (Cynthia is the name of a Moon Goddess, sometimes conflated with Artemis, Hekate and Selene) (312)

We are told that Asteria, in her efforts to escape the sexual advances of the god Zeus, fled across the land. Zeus transformed himself into an eagle to gain an advantage over her, but Asteria was keen to guard herself against Zeus, and turned herself into a quail (Ortygia) and threw herself into the ocean, becoming an island. This excerpt from Callimachus provides more detail: “But no constraint afflicted thee, but free upon the open sea thou didst float; and thy name of old was Asteria, since like a star thou didst leap from heaven into the deep moat, fleeing wedlock with Zeus. Until then golden Leto consorted not with thee: then thou wert still Asteria and wert not yet called Delos. Oft-times did sailors coming from the town of fair-haired Troezen unto Ephyra within the Saronic gulf descry thee, and on their way back from Ephyra saw thee no more there, but thou hadst run to the swift straits of the narrow Euripus with its sounding stream. And the same day, turning thy back on the waters of the sea of Chalcis, thou didst swim to the Sunian headland of the Athenians or to Chios or to the wave-washed breast of the Maiden’s Isle, not yet called Samos – where the nymphs of Mycalessos, neighbours of Ancaeus, entertained thee…” (324)

3 – Ruins of the Temple of Apollo, Ortygia (Syracuse, Sicily) at night (366)

Asteria is not known to have other children attributed to her, and Hekate is specifically named as an only child. (379)

the Theogony, Perses is the son of Eurybia (Wild Force) and Crius (Ram/Ruler), husband to the star goddess Asteria and father to Hekate. His name is usually taken to mean destroyer, and sometimes as from Persia. Hekate is also occasionally said to be Persian – a reference either to being her father’s daughter, or possibly indicative of having Persian origins. (386)

Perses’ brother Astraeus is associated with the stars and planets, and, like Perses’ wife Asteria, is a stellar deity. With Eos, the goddess of the dawn, he fathered the Anemoi. These are the four winds: Boreas, Zephyrus, Notus, Euros, and also Eosphoros (Morning and Evening Star), associated with the planet Venus. This is interesting because Pausanias recorded that Hekate was worshipped with offerings in four pits by the altar to the Four Winds in Sikini. Perses’ other brother, Pallas, was married to Styx, goddess of the underworld river and the personification of hatred. Together they bore Nike (Victory), Kratos (Strength), Zelos (Rivalry) and Bia (Force). Pallas was vanquished by Athena, who also held the title Pallas as an epithet. This makes Boreas, Zephyrus, Notus, Euros, Eosphoros, Nike, Kratos and Zelos paternal cousins of Hekate according to Hesiod’s cosmology. (408)

Phoebe, whose name is translated as bright or shining, was the grandmother of Hekate and mother of Asteria according to Hesiod. Like her daughter Asteria, and her grandchildren Hekate, Artemis and Apollo, she was closely associated with prophecy. Phoebe is named as the goddess of the Oracle at Delphi before Apollo. In the Aeschylus’s play Agamemnon, we hear the Pythia speak: “First, in this my prayer, I give the place of chiefest honour among the gods to the first prophet. Earth; and after her to Themis; for she, as is told, took second this oracular seat of her mother. And third in succession, with Themis’ consent and by constraint of none, another Titan, Phoebe, child of Earth, took here her seat. She bestowed it, as birth-gift, upon Phoebus [Apollo], who has his name from Phoebe.” (418)

“Hekate whom Zeus the son of Kronos honoured above all. He gave her splendid gifts, to have a share of the earth and the unfruitful sea. She received honour also in starry heaven, and is honoured exceedingly by the deathless gods . . . For as many as were born of Gaia [Earth] and Ouranos [Heaven] amongst all these she has her due portion. The son of Kronos [Zeus] did her no wrong nor took anything away of all that was her portion among the former Titan gods: but she holds, as the division was at first from the beginning, privilege both in earth, and in heaven, and in sea. Also, because she is an only child, the goddess receives not less honour, but much more still, for Zeus honours her.”[21] Gaia, Ouranos and Pontos are primordial gods, with each of them in turn, being the physical Earth (Gaia), Heavens (Ouranos) and Ocean (Pontos). They are not just associated with the respective domains, rather they are the domains themselves. (444)

Virgin, Wife, Mother or Lover? Hekate is never explicitly described as the wife of any of the gods, as such she remains an independent and wandering goddess, free from the ties of marriage. She is frequently described as a virgin or maiden goddess, but she is also sometimes linked to male gods and said to have offspring with some of them. These contradictory descriptions should be understood in the context of the culture, time and place. Hekate was a goddess of many forms, and her cult subsumed that of other deities along the way, incorporating aspects of their histories and worship in the process. For example, Persephone was the Virgin (Kore) before she was abducted by Hades, becoming his wife as well as the Queen of the Underworld. Yet, Persephone, for some, remains a symbol of virginity and youth, whose yearly return to the world of the living is closely linked with the agricultural growth cycle. (466)

Hekate continued to be described as a virginal goddess throughout the history of her worship. In the third century CE Lycophron Hekate is described as: “The maiden daughter of Perseus, Brimo Trimorphos…”[22] In the PGM, dated to between 200 BCE and 500 CE, we find references to virginity in several invocations involving Hekate. For example, in the Charm of Hekate Ereschigal against fear of punishment, we read: “I saw the other things down below, virgin, bitch, and all the rest”[23] And in the Chaldean Oracles of the second century CE: “I come, a virgin of varied forms…” [24] Hekate is also named as a maiden by Pindar (522-443 BCE) in his Paeans, where he includes a proclamation by the goddess in an oracle. The extract may have been a song sung at her shrine to remind locals of a victory[25] or as part of a festival honouring Apollo: “The virgin with the red border, kindly Hecate, was the messenger for the word which wanted to come true. “[26] Depictions of Hekate before the twentieth-century ordinarily show her as a young woman, or a lady of indeterminate age. She takes on many forms, single, triple and sometimes zoomorphic. (475)

The number three is also an important symbol associated with Hekate. (502)

Hekate is named explicitly as the teacher of the young Medea in the Argonautica: “There is a maiden, nurtured in the halls of Aeetes, whom the goddess Hecate taught to handle magic herbs with exceeding skill all that the land and flowing waters produce.”[36] Medea’s story is one of prodigious power and love, a story which ultimately ends in tragedy. She is associated with Hekate as a Priestess, describing the goddess as “the mistress whom I worship above all others and name as my helper”[37]. She also attributed her power to Hekate saying that “provided the triple-formed goddess helps and by her presence assents to my great experiments. (562)

Hekate is a goddess of many names. This is emphasised in both the PGM and in Proclus’ Hymn to Hekate and Janus where she is referred to as many-named. Nonnus similarly alludes to Hekate as being a goddess of many names, in his fifth century CE Dionysiaca: “If thou art Hekate of many names, if in the night thou doest shake thy mystic torch in brandcarrying hand, come nightwanderer…”[43] The understanding different groups of people hold of a deity often change over time. These changes are frequently natural adaptations to an ever-evolving culture, or variations reflecting a changing landscape due to industrialisation or migration. Religious and ritual practices evolve with what is available. For example, as different foods and plants become available the aesthetics and ingredients of offerings will change, albeit in a way which preserves something of the original. (609)

Epithets are windows back in time to how people in different places and times understood a deity, whilst simultaneously telling us about the history of deities whose cults influenced that of the god we are examining. (626)

Hekate may have the same root as Hekatos, which is the masculine version of the name and means ‘worker from afar’. Hekatos was a prevalent cult title of Apollo. This title denotes Apollo’s skilled use of his bow and arrows, and there is no reason why Hekate as the female version of the name should not be taken as having the same meaning. (634)

Hekate is on occasion shown with a bow and arrows, but such depictions are rare, and no explanation is offered in surviving myths. (640)

Another theory is that the name Hekate may have been derived from the Greek word εκατό (ekato) meaning hundred. Hecate (with a c) is the Roman Latin transliteration of Ἑκατη. Using Hekate rather than Hecate is a personal preference. Both transliterations are correct, and could be used interchangeably. (651)

Any attempt to try and understand Hekate by putting her in a tidy box and mark it with her name, will only lead to complications and a lot of (needless) headaches. In her role as goddess of the threshold and of gateways, Hekate uniquely interacted with a multitude of other deities, as she was often worshipped at city gates and at the entranceways to the temples of other gods. Gateway and entranceway shrines may have been smaller, however they would have been a constant reminder of the presence of the deity to all who entered and left. They were not insignificant. (660)

Hekate and Artemis are frequently conflated from the fifth century BCE onwards. Sometimes they were merged as Artemis-Hekate, and at other times they were simply thought to be the same goddess. They both also maintain their independence as individual goddesses, being cousins in Hesiod’s Theogony, and portrayed as taking different parts next to each other in selected myths. (698)

When Hekate gains an association with the Moon in later literature, she is paired with Apollo, the brother of Artemis, who then becomes equated to the Sun. In so doing Hekate and Apollo replace Selene (Moon) and Helios (Sun) as the deities of the Moon and the Sun. (702)

that Hekate may have been an aspect of Artemis which gained popularity in its own right. Similarly, they may have been closely connected with an earlier cult, likely that of the Phrygian Great Mother. It might also be pure coincidence and the various associations could be explained by similarities they held in common with subsequent syncretising. (713)

“The spear of Hekate of the Crossroads Which she bears as she travels Olympus And dwells in the triple ways of the holy land”[48] By the fifth-century BCE, when Bendis’ worship spread to Athens, Hekate’s cult was gaining in popularity in the city. If Thrace was Hekate’s homeland, the Indo-European and Middle Eastern influences associated with Hekate might be explained by the influence of Bendis on the torchbearers’ cult. (726)

Hekate was equated to the Roman virgin goddess Bona Dea (the good goddess). Hekate and Bona Dea are both associated with snakes, knowledge of pharmakeia and healing and both are named explicitly as virgin goddesses. The genuine identity of Bona Dea was considered an initiatory secret, and the knowledge of her true name was closely guarded. Bona Dea was linked to the worship of Hekate, Demeter, Ceres as well as to Medea, and many other goddesses. Based on the available evidence it is conceivable that Hekate was somehow associated with this Roman cult. Brimo “The maiden daughter of Perseus, Brimo Trimorphos”[52] Brimo was a name given to a Thessalian goddess of the underworld. Her name was invoked and used in conjunction with that of Hekate from the fifth century BCE, and was also given as an epithet for Persephone, Demeter and Kybele. Brimo can be translated as terrifying. (754)

Demeter, Persephone and Hekate form a formidable trio of goddesses synonymous with the Mystery Cults of Greece, especially at Eleusis. The three goddesses each maintained their own separate identities were also conflated with one another. Hekate is equated with Persephone, and also with Demeter. It is possible that some of the conflations were due to misunderstandings due to the goddesses’ close relationship at major cult centres such as Eleusis, Selinunte and Samothrace, and frequent depictions of them together. Tempting as it is to speculate that Hekate’s triplicity is somehow linked to the connection between Demeter, Persephone and Hekate, there is no evidence to support this. If there were a connection, three-form images of Hekate would be expected to somehow reflect this connection, which they don’t. Historical triple images of Hekate always shows three similar, often identical women, even when they are holding different objects. (794)

“In Nemi Diana/Artemis was venerated as a goddess of the crossroads, as a triple goddess, trivia, and as such had several functions. She was a nature deity, …but also of the moon and the darker sides of nature, and she was also venerated as a protector of women and childbirth” (808)

Diana’s cult became one of the most loved and wide-spread cults of the Roman Empire. Hekate and Artemis are both persistently equated with Diana, just as they are with one another. In Aricia Diana shared the title of Trivia with Hekate, giving her a three-fold nature. Horace named her as Diva Triformis and Catulus (149–87 BCE) named her as Diana Trivia (812)

The Nemoralia, the famous festival of Diana which started at Lake Nemi, lasted for three days, during the mid-August period (13th to 15th). The poet Ausonius remarks in his Idyll, that the Ides of August is dedicated to Hekate of Latonia [Leto]: “Sextiles Hecate Latonia vindicat Idus.”[59] These dates are also associated with Hekate at her temple in Lagina, Caria. (830)

Some contemporary worshippers honour Hekate on the 13th or the 16th of August as a likely continuation of this feast. (838)

Diana and Hekate both continue to be associated with the practice of magic and witchcraft. Diana is, for example, the goddess of The Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches by Charles G. Leland, a text which had a monumental, but sometimes overlooked, influence on the development of initiatory Wicca and subsequent Goddess and Pagan traditions of the 20th century. The first part of The Charge of the Goddess, which is one of the key texts of Gardnerian Wicca, is taken nearly verbatim from this 1899 text: “When I shall have departed from this world, Whenever ye have need of anything, Once in the month, and when the moon is full (850)

Diana became the Goddess of Witches, and the Faerie Queen and was linked to the practice of magic, superstition and the occult. But where there are stories of Diana, there are whispers of Hekate – and like Diana, Hekate appears as the Faery Queen in Scottish folklore[62]: “In Scottish lore, Hekate was often equated with the Faery Queen of the Unseelie court, Nicneven, who dwelt in the mountain Ben Nevis…”[63] The continuous association of Diana with witchcraft, together with the conflation of Diana with Hekate most likely contributed to some of the associations Hekate has with witchcraft today. (881)

“‘Enodia’ expressed Hekate’s connection with roads – specifically places where three roads meet.” (891)

In Hippocrates’ work Hekate-Enodia is named as being associated with the nocturnal attacks of ghosts and bad dreams (nightmares). Under this name she was also frequently named as being associated with the souls of the dead[65], and witchcraft. Dogs were sacrificed to Enodia, and it may also be through this divine fusion that dog-sacrifices came to be associated with Hekate. (902)

Hekate is also referred to and equated to Mene, one of the fifty daughters of Selene. Mene was the name of the daughter who presided over the months, which were calculated by the phase of the Moon. This group of goddesses were so closely associated with each other that on occasion they were considered entirely interchangeable. Kotansky emphasises this, writing that: “By the time of the writing of the Greek Magical Papyri, in fact, Artemis-Hekate-Selene-Mene-Persephone were so intimately intertwined that any differentiation between them as archetypal moon goddesses and earthly, netherworld figures was impossible.” (927)

Hekate and Isis had many points of commonality and became merged into Isis-Hekate. Jackson discusses one example of such an amalgamation in her book Isis: “Magic is a major aspect linking Isis to Hekate. There is a bronze statue in Rome that depicts Hekate wearing the lunar crown of Isis, topped by lotus blossoms, and carrying a lighted torch in each hand. The statue is dedicated to Hekate and Serapis from someone who was saved by them from an unnamed danger. Both Isis and Artemis are shown carrying a torch as is Torch-bearing Hekate who illuminates the secrets of the underworld.”[69] This is not an isolated example. Isis-Hekate was shown on coins, including lead tesserae from Memphis. Minted during the Roman period one such example depicts Isis-Hekate with three faces, crowned with a horned crown, next to the Apis bull and another smaller human figure – possibly Isis-Hekate similarly appears on intaglios (engraved gemstones) in triple form, holding serpents, swords and torches, items associated with Hekate.(957)

10 – Statue of Hekate holding a child, with a dog next to her.(959)

The Egyptian collection in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens features a bronze statue of Isis entitled Isis-the-Magician. This image, which shows Isis with three faces. is likely a Hellenic depiction inspired by Isis’ conflation with Hekate. (976)

“In fact Hekate appealed to the later imagination more as an infernal power than as a lunar; she borrows her whip and cord from the Furies…”[71] The Erinyes (or Furies) are depicted as three unpleasant looking women, sometimes robed in black. They are not part of the heavenly gods of Olympus. Instead they dwell with Hades and Persephone alongside the spirits of the dead. The primary function of the Erinyes is to uphold natural balance, protect strangers and firstborn children, and to punish oath-breakers. They are primordial forces of nature. The goddess Hekate in her triple form and the Erinyes, in addition to both being shown as three women, also share a remarkable number of important symbols. If there is an unknown syncretisation between Hekate and the Erinyes, this may provide additional clues to Hekate’s three-form nature. (989)

There are hundreds of epithets associated with Hekate. Epithets are like surnames, generally added to that of the deity, but in some instances used instead of the primary name the deity is known by. Epithets are frequently employed in hymns and invocations, and provide both scholars and devotees with insights into the nature of a deity. (1029)

Epithets may indicate a link to a particular location. Hekate Propylaia (by the gate) is a reference to the placement of shrines to the goddess in gateways. Polyonymy, the use of many names for the same thing. A good example of this can be seen in the Metamorphosis[78] where the names of dozens of goddesses, including Hekate, are said to simply be other names for Isis. (1044)

Hekate has hundreds of epithets attributed to her at different times, and in different places, during her long history of worship. With a thriving international cult today new attributes and with them new epithets continue to emerge.(1049)

Kynegetis Leader of dogs Lampadephoros / Lampadios Bearer of a lamp Mastigophorous Whip-bearer Melinoe Possibly ‘quince-coloured’. a yellow colour associated with death, or ‘dark-minded’ Meter Theon Mother of the Gods Parthenos Virgin (1079)

Propylaia Before the Gate Soteira[82] Saviour Skylakitis Protector of Dogs Tauropolos Bull-faced Trimorphos, Triformis Three-formed Trioditis Three-roads Trivia Three-ways (1101)

The Wandering Goddess “…night-wandering Hekate…”[83] Historians continue to piece together the silent history of the Greek Dark Ages (circa 1100-700 BCE) and the mysterious, culturally, and scientifically advanced Mycenaean and Minoan civilisations which preceded it. We have no real evidence for Hekate before the early Archaic Period (circa 800-700 BCE), but we do know that during this period her worship appears to be already well established in some regions. There are many debates aimed at determining which region Hekate was originally from. It is possible to argue that Hekate originated in Asia Minor (especially from Caria in Anatolia), or that she is Thracian, hails from Thessaly, or that she was Attic or more specifically Athenian. Scholars have, and will continue to debate the matter as new evidence and different ways of thinking surface. Hekate makes her literary debut in Hesiod’s Theogony which was written only (1118)

The aim of this chapter is to introduce a selection of locations at which Hekate was historically worshipped, with the hope of illustrating the diversity of reverence, as well as interesting similarities, and curious practices which are usually overlooked. “…wandering through the heavens…” (1151)

The Temple of Hekate in Lagina, is believed by some scholars to be the homeland of Hekate due to the prevalence her cult had in the region. (1165)

Hekate was also equated to Diktynna the Cretan Virgin Goddess associated with hunting and fishing. To escape the advances of King Minos, who fell in love with her, she threw herself into the sea. Rescued by fishermen she was taken to the island of Aegina, where it is likely her cult continued as that of the goddess Aphaia. Aegina, was also recorded as being the site of an important Mystery cult dedicated to Hekate. Like Diktynna, Aphaia was equated to Artemis and also to Britomaris, all of whom are associated with dogs. (1200)

Lagina is the largest known temple which was dedicated entirely to Hekate and is famous for being the site of a key-bearing procession. In this procession, a key was carried by a young girl along the Sacred Way, an 11km road which connected the temple at Lagina to the nearby city of Stratonicea. Unfortunately, we don’t have reliable information on the purpose of the ceremony. (1209)

“None of our sources explain what it was supposed to accomplish, but if it took its name from a key that was carried, then that key must have been of central importance – it must have been used to lock or unlock something significant.” [89] Johnston further explains that although we don’t know what the key opened, the number of inscriptions naming the festival indicates that it was a significant festival. We can speculate that it was the key to the city, the key to the temple at Lagina, or the key to another (unknown) precinct. Considering Hekate’s ability to traverse between the worlds of the living and the dead, it is conceivable that the key opened the way to some form of ritual katabasis. At Lagina, the goddess Hekate was given the epithet Kleidouchos (key-bearer), so it is also possible that the young girl who carried the keys in the procession represented the goddess in the ceremony. The friezes, which once decorated the temple, depict scenes which chronicled events which were significant at Lagina. Interpretation of the friezes is however incomplete, and some aspects of them appear to be unique to Caria. (1213)

Hekate assists in childbirth: “And the son of Cronos made her a nurse of the young who after that day saw with their eyes the light of all-seeing Dawn. So from the beginning she is a nurse of the young…”[90] And Hekate decides who wins in battle: (1240)

In the Hellenistic period, Hekate was given titles which included megistē (greatest), epiphanestatē thea (most manifest goddess) and saviour (Soteira) in Caria. This according to Johnston suggests that she was the leading goddess of her own city and also that Hekate played the same roles in Caria as Kybele did for Phrygia, taking the part of a city goddess and benefactress[93] (1265)

Antioch was also home to an underground temple dedicated to Hekate which could be reached only by descending 365 steps. (1366)

Hekate’s shrines are usually found by or in front of entranceways, but at Ephesus, her shrine stood behind the temple. Here visitors were warned to not gaze upon the image of the goddess made by the sculptor Menestratus: “…and there is a Hecate of his at Ephesus, in the Temple of Diana [Artemis] there, behind the sanctuary. The keepers of the temple recommend persons, when viewing it, to be careful of their eyes, so remarkably radiant is the marble…”[102] It is conceivable that this statue was of Hekate as Phosphoros, the form in which Hekate appeared as luminous light. Could the unusual characteristics associated with the radiance of this statue have been the reason for Hekate’s shrine having a place behind the temple, rather than by its entrance way? Maybe Hekate’s shrine was part of an older temple or sanctuary, which survived or continued on after the historic fire. Additionally, there is some evidence suggesting that the Temple of Hekate at Ephesus was in, or otherwise contained, an underground chamber or cave. (1410)

Hekate of Athens “I have heard it foretold, that one day the Athenians would dispense justice in their own houses, that each citizen would have himself a little tribunal constructed in his porch similar to the altars of Hecate.”[124] Aristophanes may have been exaggerating the popularity of porch shrines in Athens dedicated to Hekate in order to prove his point, but we know that Hekate was a very popular goddess in the ancient city. In addition to the household shrines, Hekate received worship and honours at numerous public sanctuaries and shrines. By the 1960’s evidence for twenty-two Hekataia and Hekate-Herms have been found in the Agora during excavations[125]. (1633)

The Triangular Shrine, in the Athenian Agora must be one of Hekate’s most impressive shrines in the city, certainly one of the oldest. It is located at the crossroads outside the south-west corner of the ancient Agora, and is, as the name suggests, triangular in shape. Activity on the site is believed to date to around 700-800BCE, with the construction of the final triangular shrine dating to around 450 – 400 BCE. The shrine remained in use well into the Roman period. In addition to being at a crossroads, its proximity to the cemetery may indicate a connection to ancestor worship. Another sanctuary or temple to Hekate in Ancient Athens stood at the site which is now home to the church of Saint Photini. This is located near the Temple of the Olympian Zeus and the Athens Gate. Photini means Enlightened One and this Saint is said to have been the first to proclaim the gospel of Christ. (1664)

Hekate is frequently depicted alongside Demeter and Persephone, forming a trio of goddesses, who when shown together are synonymous with the Eleusinian mysteries. This is how they are depicted on reliefs found at Eleusis, on Attic red-figure vases with themes related to Eleusis, and in many other locations where the Eleusinian mysteries were influential. The three goddesses are also recurrently mentioned in literature as being associated with the mysteries at Eleusis. There can be no doubt that all three these goddesses were essential to Eleusis and the Mysteries celebrated there. (1774)

There are several theories centred around the idea that the Eleusinian Mysteries involved the use of a psychedelic or otherwise mind-altering drug as part of the Kykeon drink. Participants drank this drink, which the goddess Demeter also drank, ending their fast. Opinions on what it contained vary wildly and include the use of alcohol, magic mushrooms, ergot[139], and opium. Hekate has a close association with herbal knowledge and use, and for this reason, I include an overview of the most prevalent theories here.

Magic mushrooms’ dosage is easier to control, and it is less likely to have induced such extreme side effects. However, there is no clear visible evidence of mushrooms as symbols at Eleusis, which makes the use of magic mushrooms unlikely. The poppy was one of the symbols of Eleusis, and therefore the most likely to have been employed for its active ingredients in ritual. Poppy plants produce an enormous number of seeds, and as such became used as a symbol of fecundity. Hekate and Demeter are habitually depicted as holding, or otherwise decorated with, poppy heads in the context of Eleusis. Both goddesses are also shown with the modius (grain-measure) on their heads, indicating that they were agricultural deities, so the association with fertility would have been essential. (1813)

“Hekate’s dress, an open ungirt peplos, is characteristic of young girls. Vase paintings show that in the Early Classical period, and particularly in an Eleusinian context, this image of Hekate was standard…” (1846)

Hekate is shown in a pose implying movement or running in several instances. There is an example of this on a later Roman glass paste gemstone engraved with Hekate, holding two torches aloft, where she is shown in the same pose. The intaglio is dated to around 1-3 CE and is currently in the British Museum collection. (1851)

This might seem like a contradiction, as it is not possible to be both preceding and following someone. Also, although Hekate has the ability to manifest in more than one body, which might account for this idea, she is not usually shown in triple form at Eleusis. By being both in front of and behind Persephone, Hekate takes the role of both protector and guide towards the Queen of Hades. This role held by Hekate is strangely overlooked by many contemporary scholars. Persephone’s journey is one of katabasis, travelling from the world of the living down into that of the dead, and back to the surface and the world of the living again. Hekate’s role as her preceder and follower enabling Persephone’s journey is not a simplistic role, rather it is as Johnston puts it: “one of the most difficult and significant journeys imaginable.” (1904)

Hekate’s role towards Demeter is that of benevolent mediator. She intercedes and encourages Demeter to speak with Helios, who provides Demeter with the news she was seeking so desperately. (1906)

Originally witchcraft would have been only a small part of the attributes associated with Hekate. It became more pronounced in later times and was frequently connected to the worship Hekate received in Thessaly. “Of the famous witches in literature associated with Hekate, Erictho was a Thessalian witch, and Medea gathered her herbs there.” (1954)

These offerings comprised clay vessels filled objects which typically included iron knives, jugs, pots and plates, together with the remains of puppy dogs. Several such burials have been found, but there is no indication as to why they were made or what their purpose was. Pausanias mentioned these sacrifices in Colophon, in Lydia, writing that: “I know of no other Greeks …who are accustomed to sacrifice puppies except the people of Kolophon; these too sacrifice a puppy, a black bitch, to Enodia [Hekate]. Both the sacrifice of the Kolophonians and that of the youths at Sparta are appointed to take place at night. (2015)

Hecate, or so we are told, assisted them by sending clouds of fire in a moonless rainy night; thus, she made it possible for them to see clearly and fight back against their enemies. By some sort of divine instigation the dogs began barking[164], thus awakening the Byzantians and putting them on a war footing. (2038)

Star and Crescent In Byzantium, the symbol of the upwards-pointing crescent moon and eight-rayed star (representing the sun) above it, was a symbol of Hekate, and sometimes Hekate-Artemis. The symbol may have indicated this goddess’ connection with both the moon and the sun or a symbolic reference to Apollo (or Helios) as the god of the Sun. The crescent and eight-rayed star were also sometimes used for other deities with a link to Persia and Anatolia. The crescent, with an eight-rayed star, was frequently used to depict the Babylonian goddess Ishtar and the moon god Sin. (2067)

the souls of suicide victims are amongst those said to be in Hekate’s care. In other accounts, she is transformed into a dog, an animal closely associated with Hekate. (2159)

The goddess who is thought to be Hekate is shown holding two torches and is depicted with animals, which includes a deer. It is believed that this goddess was worshipped locally by people who made their living at sea and could be Hekate, or Artemis, Diktynna or the local goddess Aphaia. The Mysteries at Aegina were popular and continued to be sought out by citizens during the late Roman Era. In one example, Paulina, the wife of Praetextatus, wrote of her husband after his death that he was a pious initiate who internalised that which he found at the sacred rites, who learned many things and adored the Divine. Paulina’s husband had introduced her to ‘all the mysteries’ and in doing so ‘exempted her from death’s destiny’. Named specifically are the Mysteries of Eleusis, Kybele, Mithras and that of Hekate at Aegina, where Paulina was a Hierophant. “… her husband taught to her, the servant of Hecate, her “triple secrets” – whatever these secrets were, the Mysteries provided less “extraordinary experience” than soteriological hope and theological and philosophical knowledge.”[176] (2188)

Hekate is named on an altar dedicated to the Sun. A curious inscription dated to between 300-100 BCE from the island of Kos, made by the (2222)

“If the patient is attended by fears, terrors, and madnesses in the night, jumps up out of his bed and flees outside, they call these the attacks of Hecate or the onslaughts of ghosts.”[183] An important feature of the Asklepion on Kos was its dream temple, where patients would sleep with the intention of being sent a dream vision regarding their ailments. Hekate’s association with dreams was enduring. Much later Eusebius, recording Porphyry’s writings in his Praeparatio Evangelica, tells us of Hekate that “As ominous dreams thou dost to mortals send.” (2248)

[Hekate] replied, ‘The body, indeed, is always exposed to torments, but the souls of the pious abide in heaven. And the soul you inquire about has been the fatal cause of error to other souls which were not fated to receive the gifts of the gods, and to have the knowledge of immortal Jove. Such souls are therefore hated by the gods; for they who were fated not to receive the gifts of the gods, and not to know God, were fated to be involved in error by means of him you speak of. He himself, however, was good, and heaven has been opened to him as to other good men. You are not, then, to speak evil of him, but to pity the folly of men: and through him men’s danger is imminent.”[188] (2311)

In Southern Italy, several dedications name Hekate as one of a trio of goddesses: Artemis-Hekate-Selene. One such example from an underground temple sanctuary found in Lipari: “The altars bears an inscription dated early 3rd century, or at least from before the destruction of Lipari in 252/1, a triple dedication to Artemis – Hekate – Selene, where Artemis has the role of Divinity of the Earth… (2328)

Hekate and Anubis are being petitioned alongside Aion and the archangels Michael and Gabriel, providing an example of how the boundaries between religious traditions became blurred from a magical perspective. (2390)

Similarly, Hekate is called upon in conjunction with the archangel Michael in a Spell to the Waning Moon, PGM IV.2241-2358. (2394)

Hekate is the foremost goddess of the Chaldean Oracles, a significant theurgic work which emphasises Hekate as being Soteira (Saviour) and as the benevolent source of souls and virtues. Hekate’s place in the Chaldean Oracles has been the subject of many studies, primarily the book Hekate Soteira (2415)

Hekate is referred to in at least 66 of the other fragments, 11 of which represent the words of the goddess herself. “…the Mistress of Life and holds the plenitude of the full womb of the cosmos.” [199] The Oracles declare that Hekate is the Soul of Nature, and also that she ensouls the light, fire, aether and the cosmos (world). “For all around the hollows of the cartilage of Hekate’s right flank, The abundant liquid of the Primal Soul gushes unceasingly, Completely ensouling the light, the fire, the aether and the Cosmoi.” (2427)

The Oracles also emphasised that Hekate was the ruler of angels, a frequently overlooked role held by this goddess. The text described the three orders of angels (‘Angelos’ meaning messenger) who serve her and aids her followers. These are: Iynges – wrynecks after the bird Synochesis – connectors Teletarchai – rulers of initiation These are the beings sent forth by Hekate when she is called upon for help according to the Oracles. The first order, the Iynges, shares its name with a magical device associated with Hekate and discussed in the chapter Magic Wheels & Whirlings. The Synochesis represent the point between things, such as the material and spiritual, the intelligible-intellective, they are a bridge on the liminal. The Teletarchai are the most important of these beings, representing the theurgic mysteries of the initiation rites. Hekate was implored in spells to send the help of her angels, for example in PGM VII we find: “…send forth your angel from among those who assist you”.[202] This not an isolated example, in the PGM’s ‘Lunar Spell of Claudianus’, Hekate is also asked to send forth her angels to assist the magician. (2439)

In Living Theurgy Kupperman provides some additional insight into Hekate’s role in the Oracles, writing about the sub-lunar Demiurge: “The virtue of Faith, Pistis, which has nothing to do with blind belief, is associated with the sub-lunar Demiurge. In the Oracles, this is represented by Hekate, Hades, and possibly Dionysos. Faith is represented by the rays of the visible sun in Iamblichean theology, and the crucified Christ in Christianity. Proclus sees it as the sole theurgic power through which union with the One occurs. Together, the Demiurges are the “Teletarchs of the mysteries,” and are engaged in the most important parts of theurgic rites.” (2462)

King Solomon Images of Hekate are frequently found on amulets and other charms. In some instances, her image or name is combined with that of Jewish divine names. An especially striking bronze amulet discovered in Southern Italy shows Hekate in triplicate form, holding her usual tools; and on the obverse side King Solomon with a wand and a container which might contain water. (2469)

Magic, like the gods, never went away either. It did what it always does, it took on the guise of the religion of its age, the techniques preserved in the pages of magical grimoires such as the popular Key of Solomon. The warnings designed to caution against the dangers of magic and the wickedness of the old gods served as inspiration for a few individuals, in each successive generation, to lift the veil and look beyond. And for many of us, Hekate lurked just on the other side, ready to inspire, and to traverse the oceans, air and land with those who knew her name, and also those who only knew her through visions and dreams. (2507)

“Now it is the time of night That the graves all gaping wide, Every one lets forth his sprite, In the church-way paths to glide: And we fairies, that do run By the triple Hekate’s team, From the presence of the sun, Following darkness like a dream, Now are frolic” (2542)

“Hekate goddess of midnight, discoverer of the future which yet sleeps in the bosom chaos, mysterious Hekate! Appear.” 1881: The Garden of Eros, Oscar Wilde “Lo! while we spake the earth did turn away, Her visage from the God, and Hekate’s boat; Rose silver-laden, till the jealous day Blew all its torches out:” (2569)

1908: The Book of Witches, Hueffer “Originally an ancient Thracian divinity, she by degrees assumed the attributes of many, Atis, Cybele, Isis, and others … Gradually she grew into the spectral originator of all those horrors with which darkness affects the imagination.” 1935 Mystical Qabalah, Dion Fortune: “To Yesod are assigned all the deities that have the moon in their symbolism: Luna herself; Hecate, with her dominion over evil magic and Diana, with her presidency over childbirth.”[206] IAO, Adonai, Sabaoth Hekate is also repeatedly implored for her assistance on amulets and defixiones in the fourth- and fifth-centuries. There are conspicuous examples of Hekate being called upon alongside, or even in some instances being conflated with the Gnostic IAO, a contraction of IHVH, the name of the Judaic God. In one example Hekate, by her name of Brimo, was merged with IAO, making Brimiao. “I invoke you by the unconquerable god, Iao Barbathiao Brimiao Chermari.”[207] In the same voces magicae (magical words) the Hebrew name Adonai (Lord) is also employed. (2577)

Gnosticism is a relatively modern term, derived from the Greek word for knowledge, to describe a variety of ancient beliefs and practices, including forms of early Christianity. Gnostics believe that the material world was created a by a Demiurge, and that the divine spark in each of us remains trapped until such time that we are able to liberate it through a divine experiential gnosis (knowledge) of it. There are some parallels with the Orphic concept of Soma Sema[209]. The Christian Gnostics made Hekate into one of their five Archons, allowing her to keep her three faces and giving her dominion over 27 demons. (2606)

Symbols associated with Hekate also appear in the fourth-century Trimorphic Protennoia: “I am the movement that dwells in the All, she in whom the All takes its stand, the first-born among those who came to be, she who exists before the All. She is called by three names, although she dwells alone, since she is perfect.”[210] Freedom and Liberty The qualities of freedom and liberty fit well with the qualities which are embodied by Hekate, and maybe for this reason so many modern devotees wonder if the Statue of Liberty (New York, USA) and Lady Freedom (Atlanta, USA) depict Hekate. While there is no indication that these gigantic statues were intended to represent anything other than personified symbolic qualities, there are some striking similarities which are interesting to consider. (2620)

Hekate is single-headed, double-headed, triple-headed and sometimes quadruple-headed. She comes with the faces of a young or adult female, but also with that of a bull, boar, cow, snake, dog, wolf, lion, dragon, goat and horse. She comes as a gentle and benevolent goddess, the saviour; and she also comes as a frightening goddess of the underworld, ruling over the souls of the restless dead. She comes known and unknown, seen and unseen, with the sound of baying hounds or the flickering of a flame marking her arrival. “…because they did not understand the character of the goddess, or that she was the very “Deo,” “Rhea,” and “Demeter” so much honoured amongst them themselves.” [214] Hekate is often named as a Triple Goddess, and in this form, she is shown as three women, of the same age, usually standing side by side, or back to back – sometimes around a central pillar. In her triple form, Hekate is shown holding a variety of objects, which typically include at least two torches. (2668)

Hekate is also recurrently depicted in a singular form, again holding objects associated with her. There are references in later texts to Hekate being four-headed, in the Greek Magical Papyri and Liber De Mensibus, as well as rare examples of what might be two-headed depictions. Her body is most often that of three women, of indeterminate age, standing around a central pillar; or of a single bodied woman standing, running/walking or seated. There are also examples of Hekate having a pillar-like body, decorated like that of Artemis of Ephesus as well as in the form of a herm. (2677)

Shapeshifting? The many forms assumed by this goddess hints that she might have shape-shifter qualities. Several of the other Hellenic deities appear to have the ability to transform their own shape (2690)

Porphyry recorded an example of offerings being made to statues of Hekate and Hermes. He accentuates the timing (New Moon) during which the rite should be done, together with details of how the icon should be treated (adoring and crowning it) and also names the offerings which were made (frankincense, wafers, cakes): “…he diligently sacrificed to them at proper times in every month at the new moon, crowning and adorning the statues of Hermes and Hecate, and the other sacred images which were left to us by our ancestors, and that he also honoured the Gods with frankincense, and sacred wafers and cakes.” (2748)

Johnston[225] says that Theopompos also recorded that images of Hekate and Hermes were washed and crowned as part of new moon rituals. Washing the statues of the deities worshipped in the home, as well as in the temples, formed a regular part of devotional practice as it kept the images clean from dust and debris. In another of his works Porphyry expressed some of the reasons behind the creation of religious statues: “… they moulded their gods in human form because the deity is rational, and made these beautiful, because in those is pure and perfect beauty; and in varieties of shape and age, of sitting and standing, and drapery; and some of them male, and some female, virgins, and youths, or married, to represent their diversity.” [226] The goddess Hekate was honoured at the gateway of the famous oracle temple of Apollo at Miletos (2754)

The evidence suggests that the earlier forms of Hekate, before the fourth century, all showed her as single-bodied. In Eleusis Hekate is most often depicted as single-bodied, holding torches or other objects associated with the Mysteries. Here a single-bodied figure of a female in a position which implies movement known as The Running Maiden was found believed to date to 460-480 BCE. Edwards[231] and other scholars have interpreted this image as representing Hekate, probably in her role as companion to Persephone. Medallions and reliefs depicting Hekate accompanying the Phrygian goddess Kybele also show Hekate as being single-bodied. In these instances Hekate is most often depicted alongside the god Hermes, accompanying, or standing with Kybele. Likewise, coins from across a broad geographic region and spanning many centuries show her with one body. (2799)

Creating three-formed icons of Hekate also fits perfectly with the goddess’ association with roads and crossroads. Depictions of Hekate gazing into three directions have a natural apotropaic symbolism and emphasises the goddess’ role as a protectress. Three-formed representations may, therefore, have been a natural development, especially if this function increased in popularity at the time. (2826)

In the Orphic Argonautica Hekate is described as having the heads of a horse, dog and lion. Here she is also described as having the ability to take on various shapes, with the animal-headed Hekate referred to specifically as being of Tartarus and as being a deadly monster. This emphasises the primordial, wild and dangerous side of the goddess, especially as she may appear to those who upset the natural balance or otherwise offend her. (2853)

The Invisible Goddess Also see: The Wandering Goddess, Hekate of Rhodes. (2887)

The multiplicity of forms claimed by Hekate in antiquity include that of invisibility, that is, no form at all. Examples of this can be seen in the cult of the empty throne at Rhodes and Chalke, where Hekate was worshipped alongside the god Zeus. The thrones add an unusual level of intrigue and challenge in the context of trying to understand Hekate through iconography, as it renders her as invisible or otherwise absent. Anatolian, and perhaps Sumerian, influence may also provide an explanation for the incidences where Hekate was worshipped, alongside Zeus, on an empty throne: “Anatolian influence is seen too in traces of the cult of the empty throne, which is Sumerian in origin, found at Rhodes and Chalke… In the rocks of Chalke, an empty throne is carved out, with a dedication to Zeus and Hekate. A Rhodian rock inscription, over a similar throne, invokes Hekate (as ‘hiera soteira euekoos phosphorus Enodia[238]’). Of clear Minoan origin is the title Zeus Kronides Anax, accompanied by the motif of the double-axe, at Rhodes.”[239] (2889)

Interesting religious counterparts centred around empty thrones can be found in contemporary indigenous tribal traditions in India today. In the state of Orisha, there are instances of tribal cults where male and female deities are worshipped as having invisible forms, seated on otherwise empty thrones or swings[242]. The Buddha was also worshipped as an empty seat, in an attempt to avoid making icons of him. The tradition and symbol of the empty throne continued into the Christian world where the empty throne became a symbol of the Son of God, in the form of the hetoimasia (prepared throne). In the examples where Hekate and Zeus are honoured together on empty thrones, it is interesting to consider the relationship this implies they may have been understood to have. Remembering, in particular, Hesiod (700 BCE) writing that Zeus honoured Hekate “above all”, and the placement of Zeus and Hekate in the Chaldean hierarchy (circa 200 CE) as the father and mother. (2932)

“The Persephone Painter’s bell krater gives us a clue to the deeper meaning of the image [Running Maiden of Eleusis]. Persephone is represented as a bride, richly crowned and draped, a young woman at the height of her beauty and sexuality. Hekate is characterized as a younger girl by her open peplos. Demeter is a matron, the archetypal mother. The three together constitute the three ages of woman, a notion that connotes not only fertility, but also the order of life as established by Zeus. (2967)

The Maiden, Mother and Crone (MMC) construct proposes that the feminine divine is singular, manifesting in many different forms (or aspects). Adherents of this construct usually believe that ‘all Goddesses are one Goddess’ and that The Goddess manifests with three faces, representing the three phases they feel epitomise the life of a woman: Maiden, Mother and Crone. The three stages are each given attributes and used to refer both to the aspects of The Goddess and used as archetypes in ritual for women to connect with both their feminity and the Divine. MMC can provide powerful and emotional symbolic models to explore in ceremonies, especially rites of passage linked to menarche, marriage, birthing, and menopause. However, while it is undoubtedly empowering for some women, the MMC is restrictive and painful for others. (2984)

The earliest mention I have been able to find of Hekate with attributes that fit the archetype of the Crone, is in the works of the controversial magician and occult writer, Aleister Crowley. In his poem Orpheus, published in volume 3 of his Collected Works (1907), he published an invocation of Hekate beginning: “O triple form of darkness! Sombre splendour! Thou moon unseen of men! Thou huntress dread! Thou crowned demon of the crownless dead!” In the same invocation, he calls upon her as: “Hecate, veiled with a shining veil, Utterly frail” Here the use of frail might indicate that Crowley associated physical age to Hekate. It could equally be a reference to the last phase of the moon. (3013)

Hecate for the harvested corn – the ‘carline wife’ of the English countryside. But Demeter was the goddess’ general title, and Persephone’s name has been given to Core, which confuses the story.” [246] Graves played with the construct, sometimes interchanging mother with nymph, for example: “The moon’s three phases of new, full, and old recalled the matriarch’s three phases of maiden, nymph (nubile woman), and crone.” (3037)

Symbols of Her Mysteries “But, again, the moon is Hecate, the symbol of her varying phases and of her power dependent on the phases. Wherefore her power appears in three forms, having as symbol of the new moon the figure in the white robe and golden sandals, and torches lighted: the basket, which she bears when she has mounted high, is the symbol of the cultivation of the crops, which she makes to grow up according to the increase of her light: and again the symbol of the full moon is the goddess of the brazen sandals.” (3083)

Symbols can, with time become more than just the thing they were intended to represent, as each person encountering the symbol evokes it and in doing so adds something of their own lifeforce and understanding into the symbol. As such, especially in a religious context, symbols can become living entities in their own right. The objects listed here are not the only objects Hekate is shown or described as holding. As a multifaceted goddess with such a long history of worship, it would not be possible to compile a complete list of all the symbols and objects ever associated with her. This list covers the symbols most frequently related to her and instances where the symbolic association is noteworthy. (3096)

“The torches carried by the maiden at the Mother’s side are the attributes of several goddesses, but primarily Hekate.”[250] Torches are synonymous with Hekate, and she is sometimes shown with just one, frequently with two, and on a few occasions in her triple form with up to six torches, one for each arm. When she is depicted in single form with two torches, there are instances, usually associated with death-related customs, where she is shown holding one torch up to the heavens and the other down to the earth, or both torches downwards. (3103)

When wielding two torches Hekate is frequently shown as leading others, or standing in doorways to sanctuaries. This suggests that Hekate, and by extension her priestesses, were responsible for leading or guiding candidates on their journey towards initiation. The role of psychopomp is a reflection of Hekate’s role towards Persephone, guiding her throughout her yearly journeys. “Hekate’s role in the story of Persephone is that of an escort across a very important boundary; in later literature, as mistress of souls, she regularly guided the dead back and forth across this same line.”[254] Initiation often marks a new beginning, a symbolic death and rebirth during which the initiate is transformed through the experience and the new knowledge or insight they gain in the process. Hekate’s presence in this role would highlight her existing connection to the cycle of birth and death. The fire of her torches can be understood to represent life. In its wider context of Greek thought her torches may also represent wisdom and knowledge which is gained through the process of initiation. (3130)

The example of Phosphoros being petitioned in Byzantium where Hekate was called upon for protection against Philip II’s invasion was discussed previously in the chapter The Wandering Goddess, Hekate in Byzantium. In this example the goddess provided a warning in the form of dogs barking, and assistance in the form of mysterious light just when it was needed most. (3164)

Hekate is usually shown as holding two daggers in triple depictions, where the other arms are generally shown with torches and whips. On occasion single-bodied depictions show her holding one dagger, with another tool in her other hand. Whips Hekate bears the epithet Mastigophorous (whip-bearer) as a reference to the whips she is frequently portrayed with. The whip has a long history of use in many different religious customs, and it is possible that the purpose of the whip(s) of Hekate can be found in looking at some of these examples, as unfortunately information on Hekate’s association with whips is negligible. (3207)

throughout the earth, by the names of triple-form Hekate, the tremor-bearing, scourge-bearing, torch-carrying, golden-slippered-blood-sucking-netherworldly and horse riding one. I utter to you the true name that shakes Tartarus, earth, the deeps and heaven…” [262] The priests of the Phrygian goddess Kybele, the Galli (Eunuch priests) practised self-flagellation until blood flowed from their bodies to show their total dedication to the goddess. In particular, this was done on the Dies Sanguinis (the day of blood) on the 24th of March each year. This festival formed part of a longer period of celebrations dedicated to Kybele between the 15th and 27th of March, (3226)

Hekate is given the title of Kleidouchos (key-bearer), a term specifically associated with her at her temple in Lagina. Here key-bearing processions or Kleidos Pompe were held down a Sacred Way between the temple and the nearby city of Stratonicea. As previously discussed, the purpose of the ceremonial key is not entirely clear, however exploring the ideas associated with keys provide some clues. (3273)

In addition to being connected with keys, Hekate was also linked to doorways, gateways and entranceways. These are liminal points through which a person passes from inside to outside, and also the point where one is most likely to use a key. As such the key symbolises the permission to move from one place to the other. Moreover, the person who holds the key to a particular door or gate can usually be assumed to be the person in charge or at the very least a person with some accountability for what lies beyond. It is curious to note that the key in the procession at Lagina was carried by a child, rather than by someone of high rank. (3281)

Hekate’s keys are said to be the keys that open the gates to Hades, as Johnston puts it this “agrees with her duties as the guide of disembodied souls”. [266] It is also referred to in the PGM as respectively the keys that open the “bars of Cerberus”[267] and the key of “she who rules Tartaros” or the “Lady of Tartaros”[268]. Numerous ancient cosmologies teach that the world is separated into Heaven, Earth and the Underworld. To pass between these three realms, it is necessary to go through gateways between them, and it is for this reason that Hekate’s association with gateways and keys makes her such an essential ally for magicians. Indispensable to those who want to gain divine revelations by accessing the realms beyond to obtain access to the souls of the dead – a journey which necessitates passing through the gates between the world of the living and that of the dead. Keys also symbolise freedom, the ability to choose whether to enter a space and when to leave. Keys are also a form of protection, by locking an area you prevent others who do not hold the keys from entering. Keys symbolise transition, moving from one place to another across a liminal point. Today this continues as a recognisable symbol in western countries marking the change between childhood to adulthood, and symbolic keys are given to represent this transition. (3300)

In addition to Dionysos, Hekate is depicted in assembly with other serpent deities, among them the gods Aion, Asclepius, Hermes, Serapis and Chnoubis. The Maenads who had such a crucial role in the Mysteries associated with Dionysos are also described as having wild snakes in their hair: “The Fates made him perfect … the god with ox’s horns, crowned with wreaths of snakes – that’s why the Maenads twist in their hair wild snakes they capture.’[280] These descriptions are reminiscent of the Gorgon Medusa, who like Hekate held an apotropaic function. Interestingly, Medusa was one of three Gorgon sisters, all of which had serpent hair and evil-averting functions and are likely to have had their origins in ancient beliefs of the feminine divine from a time before the Greek Dark Ages. A defixio from Athens dated to the first century CE shows a three-formed Hekate, with six arms, bearing torches in the upper pair of arms, with the lower pair being serpentine.[281] Ogden highlights an example of Hekate being depicted with a serpent tail as feet, and notes that: “…a striking image of ca.470BCE, actually is the earliest positively identifiable image of the goddess to survive, represents her as an anguipede, her serpent tail making one large coil behind her clothed humanoid form, with a pair of dogs emerging as far as their forelegs (3363)

Patera & Offering Vessels “For to this day, whenever anyone of men on earth offers rich sacrifices and prays for favour according to custom, he calls upon Hekate. Great honour comes full easily to him whose prayers the goddess receives favourably, and she bestows wealth upon him; for the power surely is with her.” [287] “And propitiate only-begotten Hecate, daughter of Perses, pouring from a goblet the hive-stored labour of bees.”[288] The Theogony, like other subsequent texts, highlights the importance of sacrifices to the goddess. These offerings were ritualised with the use of special offering vessels, including the patera and jug. Hekate is shown holding a patera (offering or libation bowl) on coins from Stratonicea , Caria, the city nearest the famous temple of Lagina in ancient Anatolia. In this example Hekate is usually shown as single-bodied, with a dog by her side, holding a torch in her left hand, with the patera in her right, pouring it to the ground. Hekate is also sometimes shown holding a jug, most often an oenochoe or amphora, as depicted on carved relief of Hekate found at Aegina. (3422)

Eusebius describes her, in her association with the Moon, as holding a basket: “…and torches lighted: the basket, which she bears when she has mounted high, is the symbol of the cultivation of the crops.”[292] This is a likely reference to Hekate as the Moon Goddess, and the close association of agriculture and the lunar cycle she had. The basket is also a symbol frequently associated with the fertility of the land, a natural association for a tool which is used to hold the fruits of a harvest. The Mysteries of Dionysos also involved the use of a basket, which was used to present the sacred mask: (3462)

She has dogs as companions, and as heralds, they are said to be sacred to her and sometimes presented to her as ritual offerings. The most infamous association today is the idea that black dogs (or puppies) were sacrificed to Hekate at the crossroads. This is sometimes used as a generic, but misguided, indicator that ritual remains uncovered had an association with Hekate. Dogs were also sacrificed to other deities, as well as for the purpose of scape-goating and purification rituals. “A baying of hounds was heard through the half-light: the goddess was coming, Hecate.”[295] The sound of dogs barking is often given as an announcement of Hekate’s presence. It can be found in a variety of legends associated with Hekate, such as the story of how Phosphoros came to the aid of the (3484)

The dogs who were shown accompanying Hekate have sometimes been thought to represent the spirits of the restless dead travelling with the goddess. However, as Johnston wrote: “…its docile appearance and its accompaniment of a Hecate who looks completely friendly in many pieces of ancient art suggest that its original signification was positive and thus likelier to have arisen from the dog’s connection with birth than the dog’s demonic associations.” (3501)

Likewise, the Roman Lares, ancestral spirits of the home, were believed to sometimes take on the form of a dog or a man dressed as a dog. The much later St. Christopher, called upon frequently for protection while travelling, would also be depicted as having the head of a dog. The Chaldean Oracles mentions dogs, associating them with Physis (Nature) which it presents as an aspect of Hekate. (3611)

The goddess Selene, who is syncretised with Hekate was invoked as “Lover of Horses” in the Orphic Hymn 8, To the Moon, Selene, where she is also named as bull-horned. “Hear, Goddess queen, diffusing silver light, bull-horn’d and wand’ring thro’ the gloom of Night. … Lover of horses, splendid, queen of Night, all-seeing pow’r bedeck’d with starry light.” (3708)

Depictions of divinities in the style of Artemis of Ephesus with a pole-like body represents another probable survival of the pole symbolism found in earlier mythologies. The goddesses Artemis, Aphrodite, Hekate and Hera are all on occasion depicted with this type of body which is indicative of the eastern influences on their cults. The pole as a symbol associated with the Divine Feminine has a long and rich history in the Near East. It is this region which is also the most likely place of origin for the polos as worn by Hekate which as a headdress was given to significant mother goddesses from the Anatolia region. Those depicted with a polos, both divine and mortal, were usually authoritative female rulers. The polos is a divine headdress. The polos is somewhat similar in appearance to the modius and kalathos headdresses also worn by Hekate. They are all cylindrical, but the polos is shorter and slightly tapered outwards at the top as shown in the illustration above. Other than surviving in artwork and sculpture, no known ceremonial example of this headdress is known to have survived. This has led to speculation that it was made from wood or possibly woven from another natural material which has long since decomposed. The Biblical Goddess Asherah is possibly the best-known goddess to be associated with the worship of poles. References to her can be found throughout the Torah or Old Testament of the Bible, where she is equated to a pole. (3763)

The Phrygian cap is a pointy hat-like cap with the point flopping over. It is believed to be derived from Attis, beloved of the goddess Kybele, and hence called Phrygian. Attis, whose cult dates to at least 1250 BCE, according to legend castrated himself. This gave rise to the practice of self-castration by the Galli, the priesthood of Kybele. These men castrated themselves in public as part of their initiation and dedication to the Great Mother. Attis’ mythology is closely linked to the cycle of life, death and resurrection, and through that to the seasonal agricultural cycle. Hekate is depicted with this cap on statues and reliefs, though it is rarer than depictions showing her with a polos or modius. Depictions of Hekate with a Phrygian cap most likely indicate her conflation and relationship with Kybele. The Thracian goddess Bendis, the Persian god Mithras and the Thracian mystic poet Orpheus are all also shown wearing this particular cap on their heads.(3835)

Where depictions show seven rays, it may be symbolic of a connection to the seven wandering stars (Sun, Mercury, Venus, Moon, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter). Seven may also be linked to the seven vowels used in magical incantations. These were used for both the seven wandering stars, and associated with the Iynx in the Chaldean Oracles. It is interesting here to note that Hekate is shown with an aureole on an Apulian red-figure krater vase, dated to circa 350 BCE. The painting shows Hekate, with Hermes, accompanying Persephone and Hades, during Persephone’s return journey. Stars or Wheels: 4- and 8-rayed Circles with both four-fold and eight-fold divisions can be found associated with Hekate. The symbol can be found carved by pilgrims into the marble steps and pediment of the Temple of Hekate in Lagina. When these carvings were made is not clear, but there are dozens of examples of this symbol carved into the monument, so it must have been important in some way. Numerous other symbols are also found carved into the stones, many of which suggest magical practices. (3927)

Eight-rayed stars have a long history of being associated with solar deities, which are commonly depicted with them. Although Hekate is today considered to be a lunar deity, earlier sources make no mention of Hekate’s association with the Moon. Her later relationship with the Moon is primarily because of syncretisation with Moon goddesses, such as Selene.(3973)

On another, circa third-century CE charm made from green and red jasper[343], Hekate is shown with six such stars, three each side of her, and with the inscription on the back, four more such stars. Occasionally seven-rayed versions of this symbol are also used on images featuring Hekate, which may echo the possible symbolism for the seven-rayed headdress discussed in the section above, linking Hekate to the seven wandering stars, seven vowels and seven levels of the Chaldean Oracle Hierarchy (seven heavens). (4017)

Hekate was not initially thought of as a Moon Goddess, but as her cult spread throughout the Greek, Greco-Egyptian and Roman empires she gained lunar attributes. In his work On Images, Porphyry wrote of Hekate as being associated with the phases of the triple moon, which may have been the template for the idea of the twentieth-century Witches’ Triple Goddess. “But, again, the moon is Hecate, the symbol of her varying phases and of her power dependent on the phases. Wherefore her power appears in three forms, having as symbol of the new moon the figure in the white robe and golden sandals, and torches lighted: the basket, which she bears when she has mounted high, is the symbol of the cultivation of the crops, which she makes to grow up according to the increase of her light: and again the symbol of the full moon is the goddess of the brazen sandals.”(4029)

Evangelica, giving instruction for the creation of an icon of the goddess, which is made at the new moon:(4040)

“Pound all together in the open air Under the crescent moon, and add this vow.”[346] The twelfth-century Byzantine poet John Tzetzes identified Selene, Artemis and Hekate as the three forms of Hekate.[347] In doing so, he was continuing an ancient tradition, as evidenced in the papyri texts. Hekate-Selene was the most prominent goddess in the PGM, balancing the solar Apollo-Helios as the most prominent god. One of the earliest known literary references to Hekate being lunar can be found in the first-century CE (4042)

Images of Hekate holding a pomegranate are a reminder of her intimate and often overlooked, maybe in part secretive (and if so, deliberately obscured), association with the mysteries of Demeter and her daughter. Also see: (4101)

Cakes Different types of cakes and bread were offered to Hekate, these likely varied according to regional customs and availability. Sweet cakes or balls were offered to Hekate in devotional ceremonies. These cakes were likely made from barley sweetened with honey and it is most often the women of the household who are recorded (4136)

Paeans – Songs for the Goddess In addition to food-related sacrifices, songs and music were considered among the essential devotional offerings to Hekate. (4155)

There are also other allusions to the four elements indirectly associated with Hekate and her magic, for example in the Argonautica in a discussion about the young Medea we find: “There is a maiden, nurtured in the halls of Aeetes, whom the goddess Hecate taught to handle magic herbs with exceeding skill all that the land and flowing waters produce. With them is quenched the blast of unwearied flame, and at once she stays the course of rivers as they rush roaring on, and checks the stars and the paths of the sacred moon.”[364] All four elements are specifically highlighted here. The magic herbs (earth), flowing waters (water), flame (fire) and the stars and moon (air). (4205)

Three types of offerings were left at the crossroads for Hekate (and other crossroad gods and spirits), all of which were ritualised but for different purposes. These were: katharmata (‘offscourings’) katharsia ‘(cleansings’) oxuthumia (‘sharp anger’). In addition to the above, offerings linked to specific spells may have been made at crossroads, as well as the Hekate Suppers (deipna) and possibly other devotional offerings. Not all offerings at the crossroads to Hekate would have been a Hekate Supper and though it is possible that katharmata, (4244)

The triekostia, rituals on the thirtieth day of the month, i.e. the last day of a lunar month (dark moon) were dedicated to the dead. (4287)

The Hekate Deipna (Suppers) left for Hekate at crossroads at the dark moon is perhaps the most frequently spoken of ritual offerings associated with Hekate, and maybe the most speculated about. As discussed in the previous section, not all offerings made to Hekate at crossroads were necessarily Hekate Suppers, and not all offerings at crossroads were for Hekate. The reasons for offerings at crossroads were manifold. The writings of the satirist Aristophanes’ suggest that there may, perhaps, have been a charitable motivation to the suppers: (4299)

“Ask Hekate whether it is better to be rich or starving; she will tell you that the rich send her a meal every month and that the poor make it disappear before it is even served.”[375] These words are echoed down the centuries, and in the Byzantine Suda more than fourteen centuries later we find: “‘From her one may learn whether it is better to be rich or to go hungry. For she says that those who have and who are wealthy should send her a dinner each month, but that the poor among mankind should snatch it before they put it down.’ For it was customary for the rich to offer loaves and other things to Hekate each month, and for the poor to take from them.”[376] Considering the importance given to the Hekate Suppers it is perhaps surprising that not much more is known. The available information (Aristophanes and the Suda) has been interpreted as the equivalent of a modern-day charitable offering: food left by the wealthy, in the name of Hekate, which was taken and eaten by the poor. If Aristophanes was referencing a practice of offerings left out in the name of Hekate for the underprivileged at the crossroads, then these offerings could be considered a type of early charity. They then become the equivalent of the road-side kitchens created by members of other faiths, including Buddhists, Christians and Hindus to help travellers passing through, as well as the poor. There is also an echo of the equality meals offered in the cult of Zeus Panamoros, where Hekate was(4305)

Hekate’s association with childbirth brought her into the lives of women at the very liminal time of labour. Not only is childbirth painful, but it is also a dangerous time for both mother and child. Taking into consideration Hekate’s role towards the dead, Hekate’s role as child-nurse can then be seen to take on additional layers of meaning, where she is seen responsible for helping during birth, and taking into her care those who did not make it through the process. (4362)

Today, more often than not, it is the hexing (or baneful) herbs which are associated with Hekate. These are plants which are typically poisonous, and sometimes have psychoactive qualities. Curiously however, when considering the plants associated with Hekate in ancient literature and art, most them are not actually poisonous. Conversely, some were thought to be antidotes to poison, and almost all were better known for their healing qualities. (4433)

Chamomile (likely Chamaemelum nobile) Used as a strewing herb, and in washes and baths for women’s problems, and for women who were nearing birth. (4470)

(Mandragora officinarum ) [Poison] The root of this plant has narcotic and hallucinogenic properties. It was used to treat melancholy, and as a surgical sedative by ancient physicians. (4528)